v4j

Voynich for Java (v4j) library

Project maintained by mzattera Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

Note 005 - Slots and a New Alphabet

Last updated Apr. 2nd, 2022.

This note is part of my article I presented at the International Conference on the Voynich Manuscript 2022 ZATTERA (2022).

This note refers to release v.10.0.0 of v4j; links to classes and files refer to this release; files might have been changed, deleted or moved in the current master branch. In addition, some of this note content might have become obsolete in more recent versions of the library.

Working notes are not providing detailed description of algorithms and classes used; for this, please refer to the library code and JavaDoc.

Please refer to the home page for a set of definitions that might be relevant for this working note.

Abstract

I show how the structure of Voynich words can be easily described by assuming each word type is composed by “slots” that can be filled accordingly to simple rules, which are described below.

This in turn sheds some lights on the definition of what might constitute a Voynich character (the Voynich alphabet).

Given the nature of this topic, it is impossible to define rules that apply to 100% of cases; after all, syntactical and grammatical exceptions exists in any modern text as well. However, I will try to focus on claims that apply to the vast majority of cases.

Methodology

I start my analysis from a concordance version of the Voynich text (see Note 001); this is obtained from the Landini-Stolfi Interlinear file by merging available interlinear transcriptions for each transcriber. In the merging, characters that are not read by all authors in the same way are marked as unreadable. This to ensure the word types I will extract from the text are the most accurate.

For reasons explained below, any occurrence of the following characters is also marked with an unreadable character:

-

‘g’, ‘x’, ‘v’, ‘u’, ‘j’, ‘b’, ‘z’ (47 occurrences in total, 13 of them are single-letter words).

-

‘c’ and ‘h’, when they do not appear in combinations such as ‘ch’, ‘sh’, ‘cth’, ‘ckh’, ‘cph’, ‘cfh’; this sums up to 11 word types.

As a second step, tokens are created by splitting the text where a space was detected by at least one of the transcribers; there are 31’317 tokens in the text, ignoring those that contain an unreadable character.

The list of word types is the list of tokens without repetitions (this would be the “vocabulary” of the Voynich). These 5’105 total word types have then been analyzed as explained below.

Considerations

By looking at the word types in the Voynich, we can see their structure (that is, the sequence of Voynich glyphs used to write them) can be easily described as follows:

-

each word type can be considered as composed by 12 “slots”; for convenience I will number them from 0 to 11.

-

each slot can be empty or contain a single glyph.

-

the choice of glyphs that can occupy a slot is very limited and for 9 out of 12 slots it is as low as 2-3 possible glyphs.

-

each glyph can appear only in one or two slots, with exception of ‘d’ that can appear in three different slots.

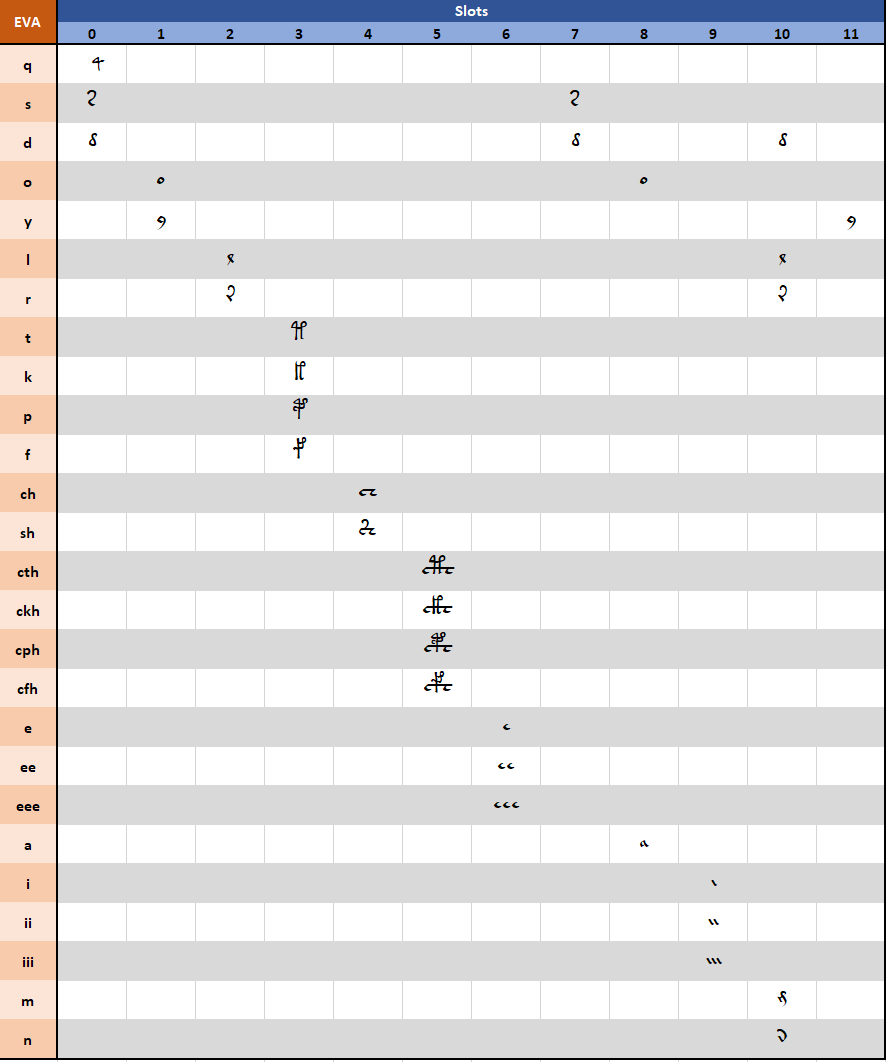

The below table summarizes all of these rules, showing the 12 slots and the glyphs that can occupy them {1}.

In some cases, the word structure can be ambiguous, since a glyph can occupy any of 2 available slots (e.g. the word type ‘y’ can be seen as a ‘y’ either in slot 1 or slot 11); following some further analysis on word structure, when decomposing a word, I always put each glyph in the rightmost possible position. Notice this is a “weak” rule that is quite arbitrary and has no impact on which word types can or cannot be described by this model.

To exemplify this concept, I show how some common word types can be decomposed in slots;

'daiin'

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ d ] [ a ] [ii ] [ n ] [ ]

(notice 'd' is in slot 7 and not 0, even if both position would be legit)

'qokeedy'

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

[ q ] [ o ] [ ] [ k ] [ ] [ ] [ee ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ d ] [ y ]

(notice 'd' is in slot 10 and not 7, even if both position would be legit)

'chcthor'

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ch ] [cth] [ ] [ ] [ o ] [ ] [ r ] [ ]

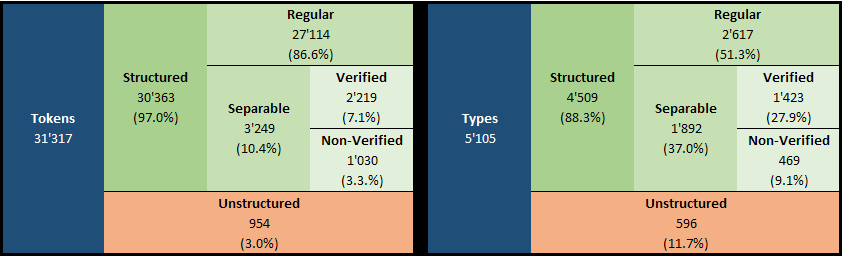

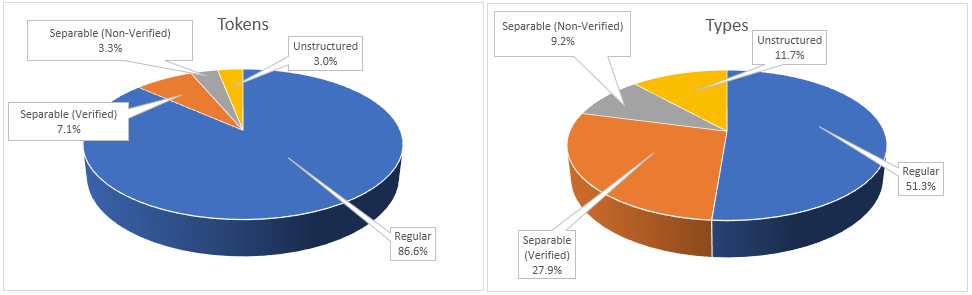

We can then see {2} that tokens can be classified as follows:

-

27’114 tokens (86.6% of total), corresponding to 2’617 different word types (51.3% of total), can be decomposed in slots accordingly to the above rules. I will call these tokens “regular”.

-

3’249 tokens (10.4% of total), corresponding to 1’892 different word types (37.1% of total), can be divided in two parts, each composed by at least two Voynich glyphs, where each of these parts is a regular word type. I will call these tokens “separable”.

Moreover, we can see that for 2’219 separable word types (75.2% of total separable word types) their constituent parts appear as tokens in the text at least as often as the whole separable word type. For example, the word type ‘chockhy’ appears 18 times in the text; it is a separable word type that can be divided in two parts, each one being a regular word type, as ‘cho’ - ‘ckhy’ which appears in the text 79 and 39 times respectively. I think this is an indication that many separable word types are possibly just two regular words that were written together (or the space between them was not transcribed correctly). When I need to distinguish these word types from other separable word types, I will call them “verified separable” or simply “verified”.

-

Remaining 954 tokens (3.0% of total), corresponding to 596 different word types (11.7% of total), are marked as “unstructured”.

Notice that 489 out of these 596 word types, or 82%, appear only once in the text; this percentage is 59.8% for regular and separable word types considered together. This might suggest that unstructured words are either typos or special words that are encoded differently than other words.

-

Sometime I contrast regular and separable word types to unstructured ones by calling the former “structured”.

The below tables summarize these findings.

In short, almost 9 out of 10 tokens in the Voynich text exhibit a “slot” structure. Of the remaining, a fair amount can be decomposed in two parts each corresponding to regular word types appearing elsewhere in the text. The remaining cases (3 out of 100) are mostly words appearing only once in the text.

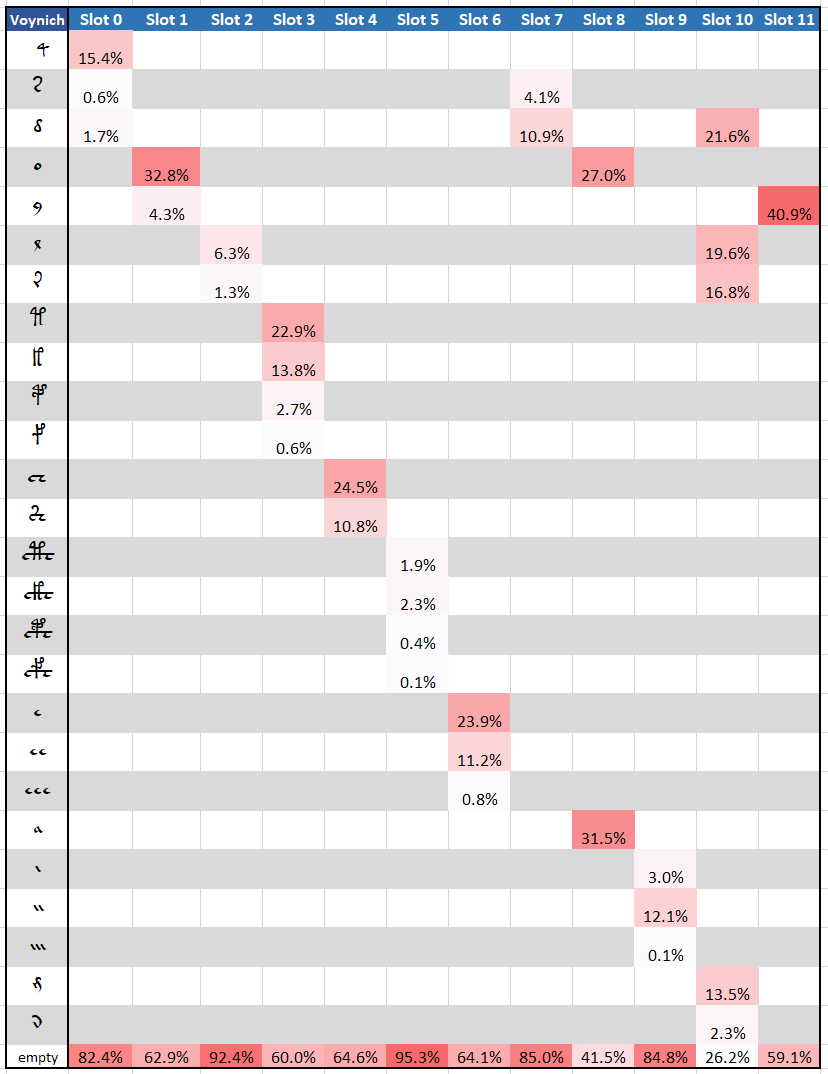

The below table shows percentage occurrence of glyphs in slots for regular word types {3}.

(it is expected the distribution to change based on Currier’s language and illustration; this is something to be further investigated).

The Voynich Alphabet

The definition of the Voynich alphabet, that is of which glyphs should be considered a single Voynich character in the text, is still open. Each transcriber must continuously decide what symbols in the manuscript constitute instances of the same glyph and how each glyph needs to be mapped into one or more transliteration characters.

However, if we consider the above defined slots as relevant for the structure of word types, we can reasonably assume that each glyph appearing in a slot constitutes a basic unit of information, that is a character in the Voynich alphabet. As far as I know, this is the first time that a possible Voynich alphabet is supported by empirical evidence of an inner structure of Voynich word types.

Below, I analyze more in detail some relationships between glyphs, as they appear in slots, and EVA characters.

Rare Characters

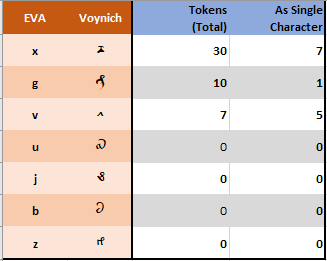

Some EVA characters seldom appear in the original interlinear transliteration {4}, end even less frequently in the concordance version used, where they appear mostly as single characters, as shown in the table below (which also considers “unreadable” tokens). For this reason, I decided to ignore these characters and mark them as “unreadable character” for this analysis.

Notice that through the Voynich there are several glyphs which cannot be directly transliterated into EVA characters (so called “weirdoes”); they are ignored by most authors in any analysis of the text.

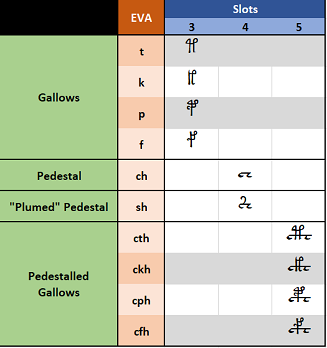

Gallows and Pedestals

Some glyphs (EVA ‘t’, ‘k’, ‘p’ and ‘f’) appear taller than other characters and are traditionally referred to as “gallows”. The combination ‘ch’ is instead called “pedestal”. Some glyphs (EVA ‘cth’, ‘ckh’, ‘cph’ and ‘cfh’) appear visually as a overlap of the pedestal with one of the gallows and are therefore called “pedestalled gallows” (or “split gallows”). These glyphs appear in slots 3, 4, and 5 and are shown in the below table.

It has been hypothesized (e.g. TILTMAN (1967) p.7 point (b.)) that pedestalled gallows might be a “ligature”, that is a more compact from of writing a combination of the pedestal and a gallows character. If we look at slots 3 through 5, we might think that pedestalled gallows can be indeed a combination of a gallows character followed by the pedestal, in this specific order. However,

-

The combination of gallows in slot 3 followed by a pedestal in slot 4 is quite common in the text. 2’185 tokens, or 419 regular word types, that is 16% of regular word types, and written explicitly as two glyphs.

-

In 332 tokens, we have a pedestal followed by a pedestalled gallows. This would correspond to a double pedestal in a word (or a separable word), which contrasts with the structure suggested by slots.

-

Gallows and pedestalled gallows are preceded by different characters (see Note 007).

This leads me to think pedestalled gallows are Voynich characters in their own, and not ligatures. Incidentally, CURRIER (1976) came to the same conclusion.

In addition, the character ‘c’ appears outside of the pedestal or pedestalled gallows only 7 times (‘c’, ‘oc’, ‘chcpar’, ‘ckshy’, ‘ocfshy’, ‘cs?t?eey’, and ‘o?cs’); similarly, the character ‘h’ appears outside of the pedestal, the pedestalled gallows or the “plumed” pedestal only 4 times (‘theody’, ‘docfhhy’, ‘cfhhy’, and ‘d?ithy’). This seems a strong indication that EVA ‘c’ and ‘h’ do not correspond to Voynich characters {5}{6}.

‘e’ and ‘i’

The characters ‘e’ and ‘i’ only appear in slots 6 and 9 respectively, in a sequence of 1, 2 or 3. Some transcribers, like Currier, have assumed some of these sequences to be a single Voynich character.

It can be argued that these are indeed repetitions of the same character but, if this is the case, as these sequences appear always in same slots, what it is relevant here would be the number of repetitions. Using an example with Roman numerals, the sequence “III” must not be understood as a 3-character word, rather as the number 3.

In addition, it should be noted that several characters in the Latin script might appear as repetitions of the same character, when written by hand; for example “m” looks like “nn”, “w” can be read as “uu”, but these are single characters.

Based on the above, I assume each sequence of ‘e’ and ‘i’ is probably a character in itself (or anyway a single “logical unit”, like in Italian where, even if “q” and “u” are distinct letters, “q” appears only in “qu-“).

The Slot Alphabet

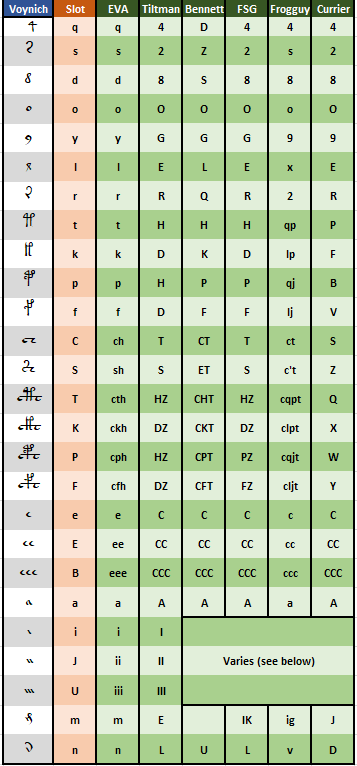

Finally, drawing from the above considerations, I propose a new transliteration alphabet, which I will call the Slot alphabet for obvious reasons.

I think that, being based on the inner structure of Voynich word types, this alphabet is more suitable than others when performing statistical analysis that relies on characters in words or when attempting to decipher the Voynich, where a one-to-one correspondence between the transliteration characters and the Voynich characters is paramount.

In addition, the alphabet can be easily converted into EVA, and vice-versa, therefore being used interchangeably.

The below table defines the Slots alphabet and compares it with other transliteration alphabets.

In some of the above alphabets, sequences of EVA ‘i’ are treated differently, depending on the letter following the sequence. Therefore, there is no unique way to transliterate sequences of ‘i’ into these alphabets without looking at the whole Voynich word being transliterated.

For Titlman, ‘p’ and ‘f’ are variant forms of ‘t’ and ‘k’ respectively; similarly ‘cph’ and ‘cfh’ are variants for ‘cth’ and ‘ckh’. I assume EVA ‘m’ is transliterated as a variant of ‘l’ (Tiltman’s ‘E’).

A transliteration

of the Landini-Stolfi interlinear file that uses the Slot alphabet is available within

v4j library and accessible using VoynichFactory factory methods.

Comparisons with Previous Works

I am not the first one analyzing the internal structure of Voynich words; as this section is going to be long and possibly continuously updated, I created a separate page.

Conclusions

-

Majority of words in the Voynich exhibits an inner structure described here, where word types can be represented as composed by 12 “slots” that can be left empty or populated by a single glyph chosen among a very limited group of glyphs (usually 2-3).

-

86.6% of tokens (51.3% of word types) exhibit this structure (regular word types).

-

10.4% of tokens (37.1% of word types) can be divided in two parts, each presenting the inner structure described above (separable word types).

For 68.3% of separable word types, their two constituents appear in the text more often than the separable word type itself (verified separable word types).

This seems a strong indication that separable word types are made by two regular word types written or transcribed together.

-

only 3.0% of tokens (11.7% of word types) do not exhibit this structure (unstructured word types).

82% of unstructured word types appears only once in the text. In other words, only 1.5% of tokens (2.1% of word types) are unstructured word types appearing at least twice in the text.

I argue that these can be typos or plain text words encoded in a different way than the majority of the text (e.g. because they represent proper names or uncommon words).

-

-

I think the above evidence supports the idea that “slots” are a significant structural component of Voynich words.

-

If so, it is reasonable to assume that glyphs appearing in slots are basic unit of information; in other words, these should be the characters of the Voynich alphabet. This led the creation of a new transliteration alphabet presented here, the Slot alphabet.

A transliteration of the Landini-Stolfi interlinear file that uses the Slot alphabet is available

-

As far as I know, Slot alphabet is the first one that is based on empirical data about the structure of Voynich words, trying to capture the intent of the Voynich author.

I think this is an important aspect to consider, both for attacking the Voynich cypher and performing statistical analysis of the manuscript, when a one-to-one mapping between the Voynich characters and those in the transliteration alphabet is crucial.

-

In addition, slots shows that next unit of information above characters are indeed words in the Voynich text. This does not mean that words in Voynich are actual words in a the plain text, but shows that they are indeed a logic building block of the text.

-

Slots should be considered when attempting to decipher the text. Whether the Voynich has been created by encoding a plain text or by a mechanical process, slots are likely to be the basis of such mechanisms.

-

Slots described here apply to the whole of the Voynich text; this was not granted, as we know there are differences in the text (e.g. different character distribution between language A and B, different word endings, etc.). This might suggest the text was generated by using the same process across the entire book. Whether the differences we see in the text are the result of different “settings” used on the process or the effect of differences in the plain text possibly encoded, is still impossible to say.

-

Since no natural language presents such an inner structure, the existence of “slots” constitutes a strong objection to any attempt to propose a simple substitution cipher for the Voynich.

This was pointed out as early as in TILTMAN (1967) (p. 9 paragraph (o)), CURRIER (1976), and also by Stolfi (see “Discussion and conjectures”).

-

Similarly, the “slot” structure of words will condition character entropy in the text, as already noted in BOWEN (2020), Therefore, attempts to assign a natural language to the Voynich by looking at similarities in character entropy seem not to be based on solid ground.

-

Because of this structure of Voynich words, removing a character in a word (that is, emptying a slot), has good chances to produce a valid word. The below table shows how many times removing a character from a Voynich word produces another word in the text (for this concordance version of the text, using the slot alphabet has been used){7}.

From Any Word From Any Word Appearing at Least 5 Times Removing any character 37.2% 65.3% Removing first character 61.5% 89.9% This is relevant, for example, in considering John Grove’s theory that many ordinary-looking words occur prefixed with a spurious “gallows” letter (so called “Grove words”).

Notes

{1} I have removed gallows and pedestalled gallows from slot 7, where they additionally appeared in earlier versions of this working note. This because my subsequent attempts at creating a state machine that models word structure lead me to believe this was a more correct and concise description.

{2} Class

Slots

has been used to perform this analysis. An Excel (Slots.xlsx) with its output can be found in the

analysis folder.

{3} Class

CountCharsBySlot

has been used to produce this table.

{4} Class

CountRegEx

can be used with regular expression [^\\.]*[gxvujbz]+[^\\.]* to find words with rare characters.

{5} Class

FindStrangeCH

can be used to list words with these “strange” occurrences of ‘c’ and ‘h’.

{6} Stolfi came to the same conclusion when defining his grammar for Voynichese words.

{7} To perform this analysis class

RemoveChar has been used.

Copyright Massimiliano Zattera.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.